Children of Buddha

Travelling in Bhutan around the typical tourist attractions, one day I arrived at a mountain monastery. It was a sunny day and there was a break in the prayers so, as ever on such occasions, the courtyard was crowded with monks. My attention was caught by a large group of small boys, about seven years old. The contrast between the childish faces and the seriousness of the monk’s robes naturally attracted attention. Instinctively, lured by the unusual quality of the situation, I decided to take a few pictures.

Before I managed to get any closer, the children were surrounded by a group of American pensioner tourists, and the whole customary ritual of tourists taking pictures of the local exotic attractions got under way. The children, treated like colourful trophies, were grouped together for collective portraits or patiently posed for individual pictures. Finally, they were given some sweets and the group disappeared, speeding up for another local attraction. I remained in the courtyard, struck by a dominant sense of absurdity, and distaste. Didn’t feel like taking more pictures.

Observing this short meeting between local children and a group of tourists, I could not help wondering what such an encounter would be like if it had occurred in Europe or the USA. After all, we would normally find it shocking to see a seven-year-old in monk’s robes living in austere conditions of a monastery. The only explanation seemed to be that, by their “otherness” these children had ceased to be human in tourists’ eyes. They had become no more than decorative elements in a photograph, not living, feeling human beings.

I lost the will to take any more photos. Instead, I felt a growing embarrassment at this total lack of empathy and compassion. I felt I could not just turn around and leave. I could not resist the question of what their childhood was like in these extremely hard conditions. Their lives would probably have been an intolerable nightmare for my children. Who had sent these children to this fate? Did they have any kind of choice? These children’s fate suddenly became important for me at a personal level. I needed to understand and tell others their story and that’s how Children of Buddha project got stated.

Most of the children in the pictures are social orphans for whom the monasteries had become the only family they could find in Bhutan. When I thought about naming them, I decided that, on having been abandoned by their parents, they had become “Buddha’s Children” in the monasteries.

Constant ringing of the monastery bell governs all important aspects of little monks’ life. A wakeup call, prayer time, beginning and end of a school day, and finally a time to bed. The same routine each day of a year with the only exception of a few religious festivities.

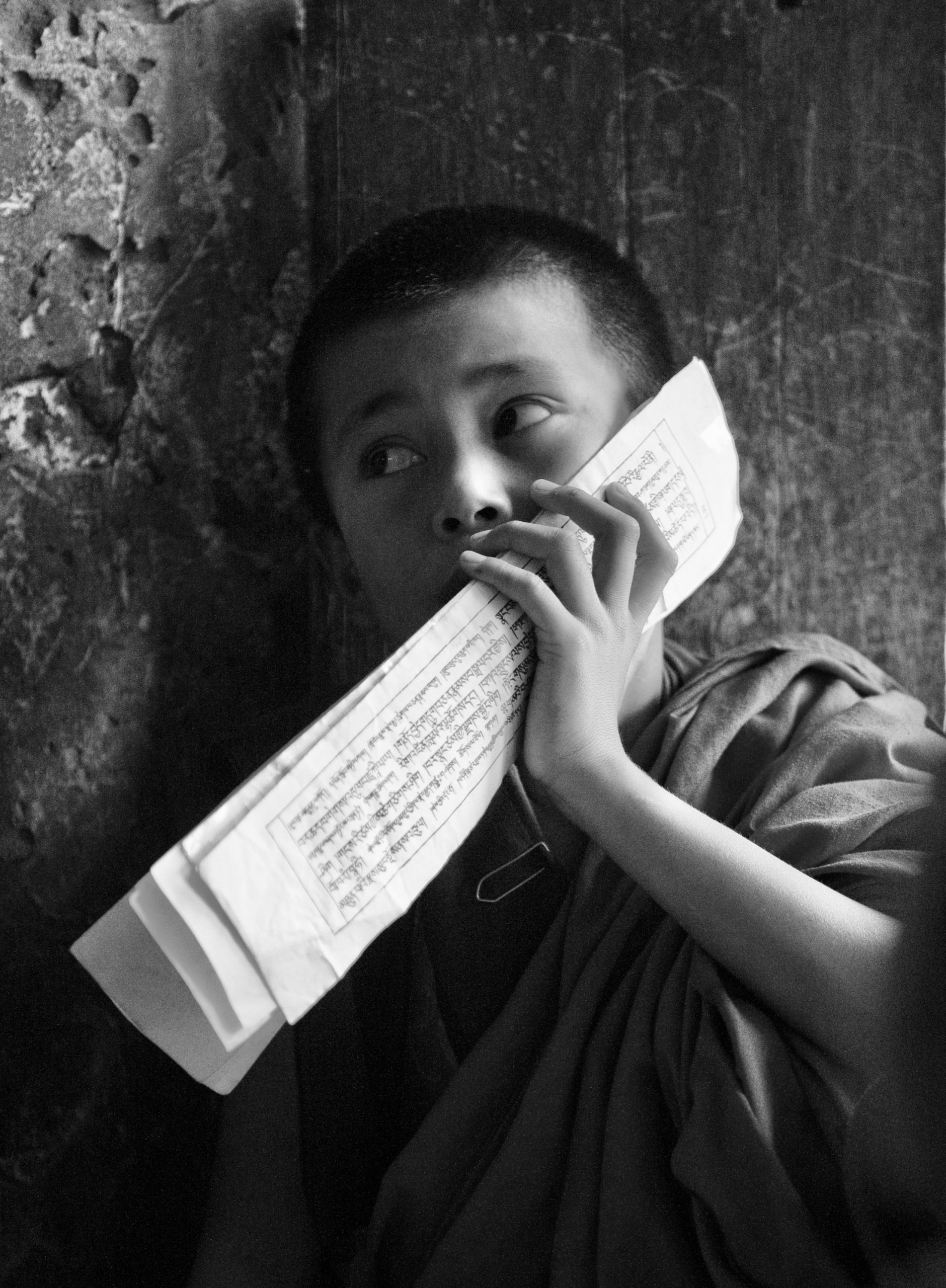

The children’s school days are divided into morning classes, when they learn by heart sacred scriptures, and afternoon examination sessions when each of them needs to recite without mistakes the entire lesson of the day.

In reality, children often don’t understand a word of what they learned, and this is not expected as the understanding is supposed to come in the future as they reach a more advanced stage.

I have looked at you through the lens of my Nikon already for quite a while, but you don’t look back. You seem to be completely lost in your thoughts. Your cheek pressed against a page of a sacred book, your lesson for today. I have a feeling that you are desperately begging this page to help you learn by heart its content. It feels so hopelessly difficult task. I guess it must be one of the sutras, Buddha’s teachings.

This thought makes me wonder how He, in his eternal wisdom, would feel knowing that in the future someone would make 10-year-olds learn his teachings by heart, probably without understanding a word. I am quite positive that He would oppose to such idea considering that learning should be a path to understanding not a ritual. It’s saddening how often we turn into mere rituals these precious moments of the here and now. Let me know your thoughts.

Dechen and Karma were inseparable friends. They always tried to protect and support each other. As boys, they could not be more different. Dechen was the best pupil of the class, very calm and well mannered. Karma was wild and strong, always happy to have a fight, lagging behind the rest of class with his learning.

They created a very special bond. Dechen was doing at his utmost to help Karma catch up with his learning and Karma was protecting Dechen against some rough boys.

When I look back at my memories from Bhutan I always wonder if their friendship has survived the test of time.

Feeling hunger is something you know all too well. Plain rice with a fistful of vegetable curry was all that you got for lunch. Not enough to feed your growing young body. So, all too often, you try to lick the last drops of the curry sauce in an almost animal way. Such a sad view and there is so little that I can do to help you.

Staple and low in nutrients monastery diet is not suitable for children or adolescent needs. Very often I have misjudged the age of children living in monasteries as due to poor diet they were significantly smaller than their peers living in nearby villages. Documenting the cases of children malnutrition was one of the critical tasks for seeking help from local UNICEF and international donors.

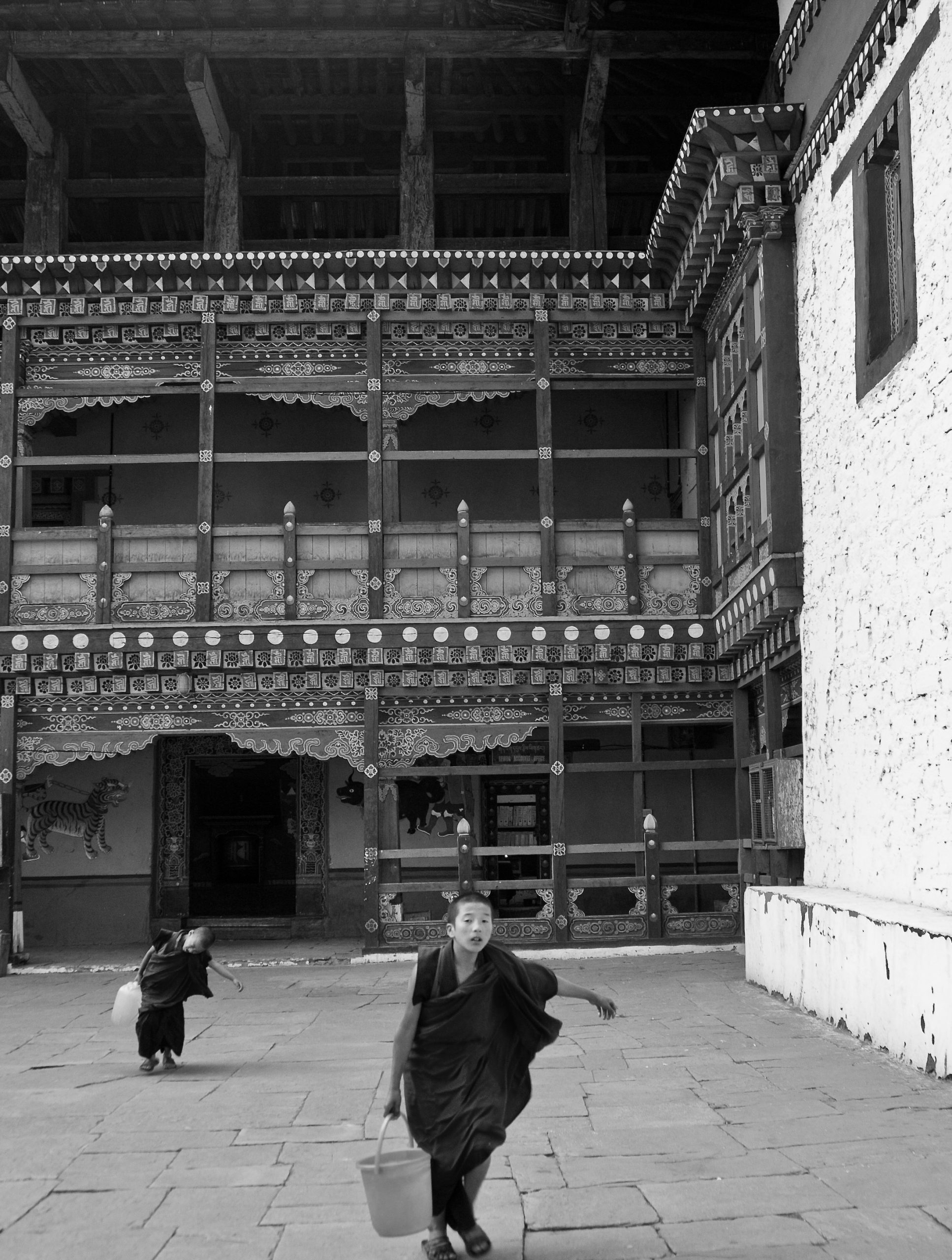

At our home, we turn the tap and can enjoy cold and hot running water as much as we please. But here, in this monastery in the Himalayas, it is a different story. Every litre of water for cooking, washing, everyday hygiene, needs to be dragged from a single well.

Children must do all the household chores as much as adult monks or sometimes even more. Carrying a bucket-load of water across the courtyard and up the steep stairs is a real challenge, especially for smaller children, not much bigger than the bucket they are carrying. It is a backbreaking work for them.

The lack of running water was also the single most important factor affecting spread of diseases among children monks, due to improper hygiene. That is why UNICEF has chosen bringing safe running water to the monasteries with children as its first goal. I was proud to be able to offer my humble pictures in support of this action.

You draw something in a sketchpad with great concentration and attentiveness. When I came to your class this morning with the abbot of the monastery with the proposal to do the first drawing class, you were the first to volunteer.

I thought for a long time about what I could do for the children here to break the monotony of the same daily routine, divided between lessons and prayer. Create a chance for the need for free expression and fun, so natural at their age.

I’ve never taught drawing lessons. All I remembered was that as a child I loved to draw and loved art classes. I just wanted to let a ray of light into your mundane, so far from the needs of a child, monastic reality.

When I asked the abbot for permission to give drawing lessons, he answered me with a smile and nodded in agreement. Overjoyed, I rushed to the town at the foot of the monastery and bought up all available supplies of crayons and drawing pads.

At the first lesson, I asked you to draw your dream. Watching you it appeared to me that probably most of you have your own crayons and a block for the first time. Many of you have never held a crayon in their hand. There is absolute, almost meditative, silence and concentration in the room. Completely different from the childish bustle that filled the classroom during my art lessons.

I am very curious what the theme of your drawings is. I peek discreetly, trying not to distract you. I see the first, second, third, subsequent drawings and I feel more and more moved. All your dreams are the same. In each drawing, I see a house and a road leading to it. God, how well I understand you…

Your name is Dorji and you are the smallest of the children monks living in this monastery. As sometimes happens, your little body contains a great spirit. You are the biggest urchin among all the kids in this monastery. Your robe is always torn, barely clinging to you.

More of a rag, than a monk’s dress, it bears witness to your restless spirit. Now, with all the focus of your little body, you draw strength from it. You want your paper plane to fly as far as possible.

Today in the drawing class I threw out the idea that I would teach you to make different paper airplanes. I wanted to use the already painted sheets of paper for new activities and then do a small flying competition in class. All the children rushed to assemble airplanes and in no time the old drawings took on the most bizarre shapes, more or less plane-like. We started the first flight tests and the whole class was filled with a din of children’s excitement.

I did not expect Dorji to suddenly give a call to move our aviation competition to monastery hill. Before I could react, all the kids were running screaming towards the stairs and soon the hillside turned into an airport full of planes taking off. Your joyful calls filled the mighty w the monastery walls, and I shared your joy, devising a prize for the farthest flight.

Suddenly, in one of the windows, I saw the silhouette of the abbot and realized how out of place all this noise must have been for him. Sensing problems, I tried to tame your spontaneous competition. The monastery bell came to my rescue, summoning you to the next lessons.

You ran to your classrooms, and I got to cleaning up – paper planes like a flock of birds covered the hillside. I sensed trouble, after all, a monastery is not a place for such frivolity. I’ll take care of these problems somehow. Your rare moments of joyful, uninhibited fun are worth such a risk.

I am trying to guess your age, looking at you through my camera. You look so small and fragile, the height of a 6-7 years old in Europe. But I know that due to malnutrition your size is deceiving. You are probably 5 or more years older. The harsh environment and poor diet make this mountain monastery not an adequate place for your development.

And then I notice how burned and damaged the skin of your face is. High in the Himalayas, the sun knows no mercy. Forgetting about sun protection means serious sunburn turning into an open wound. So, I am protecting my face with a hat and a thick layer of sunscreen. Your young skin is fully exposed to the burning summer sun or biting, freezing winds of the Himalayas’ winter. Your head is covered with wrinkles, scars, deformations as if you were an old man.

I look deeper into your eyes, but I see no pain there, just curiosity and a welcoming smile. You’re defying all these harsh and unforgiving surroundings with this simple smile of yours.

You are clenching your fists trying to look as ferocious as you can. You are ready to fight for your life and will stand your ground. Nobody is going to scare you.

The contrast of monk’s robes and fighting postures may seem strange at the first glance. But all becomes clear when I ask you about your favorite hero. It is Bruce Lee. The legendary fighter but also a rebel, famous for doing the impossible, breaking the barriers.

So, what do you rebel against? The lack of a proper childhood? Being so far away from home and family? Your fate? I don’t have the answers, but I join you in this fight for hope.

“Maybe there is a beast… maybe it’s only us.” – William Golding, Lord of the Flies

Why do you hurt this boy, this little schoolmate of yours? You feel no shame, no mercy, the air is filled with your laughter. You are overjoyed with the pain and humiliation you inflict.

Is this because the language of violence was the only language you have experienced in your short life? Or do you hate this boy because he is smarter or more diligent than you? Maybe you just enjoy violence for its own sake, and he is an easy victim?

I am terrified and I am lost. This is not something I have expected to see in the Buddhist monastery. But I have not expected either the schoolmaster walking with a whip. Is this violence that breeds violence?

You run. So carelessly, joyfully, free.

It is early in the morning and other children are rushing to the classes to be on time for the monastery school. But not you, engrossed in your own world.

You have spread your arms, as if you were flying, looking up into the sky. Free as a bird, moving effortlessly, gracefully, across the sky.

For days I have shied away from asking the question how many children monks are actually running away from the monastery back to their families.

When I finally got myself to asking it, the abbot did not seem to be offended nor surprised by the question. “Around one third of them will try to run away one day” he said.

“The families will bring them back to the monastery and then, they will run away again. When they are mature enough to take care of themselves, they will disappear for good”.

The school bell rings, and, in an instant, you stop your run. Your arms are no longer like wings gliding across the sky. Your free spirit, your joyfulness, all seems to be gone.

Piotr is now spreading his professional life across executive coaching and portrait photography. Compassion, humanity, reflection are key values in all his projects. As a photographer he worked on assignments from National Geographic, Museum of Asia and Pacific and various NGO’s. His reportage “Children of Buddha” won in International Photography Awards.

What inspires him in photography are natural portraits in available light, as he would call them “with the soul”, revealing the inner beauty of the person.

For professional assignments or artistic cooperation, he can be contacted by email: piotr.kowalski@thecoach.pl

Photographer: Piotr Władysław Kowalski @inyoursecretlife

All photographs copyright Piotr Władysław Kowalski. Any reproduction of these photographs in any format is prohibited. This means that the resale and reproduction, even partial, in any manner and form, of Piotr Władysław Kowalski photographs is prohibited. Anyone wishing to use the contents must have to ask in any case written authorization to Piotr Władysław Kowalski.